Chapter 8: Building long-term support for your digital inclusion program

No matter what your start-up program’s focus, strategy, sponsorship and initial support may be, a time is very likely to come when you’ll need funding and other material support to keep it going and growing. The more successful you are—defining “success” as the number of people your program serves—the sooner that time is likely to arrive. Even programs operating within the structures of large, stable anchor institutions, like libraries and community colleges, eventually find it necessary to raise outside money. Small nonprofit programs usually face this need from Day One.

Historically, raising money for ongoing support of community digital inclusion programs has been hard. The common funding sources for community programs—local foundations, corporate donors, local and state government—are already responding to many competing demands and seldom give priority to issues of digital literacy and access. Where local funding streams for digital literacy and access do exist, they’ve tended to take the form of small and/or short-term grants that provide little stability or opportunity for growth.

Changing this difficult funding landscape is one important goal of NDIA as well as a number of local digital inclusion coalitions (see NDIA’s Digital Inclusion Coalition Guidebook)68.

The COVID-19 crisis that began in March 2020 has altered the support environment for digital inclusion in important ways. School systems across the country, attempting to adapt to the pandemic with online learning solutions, have been forced to confront the reality that millions of their students live in unconnected homes. In many communities this has suddenly turned the digital divide into an emergency, with state and local governments, foundations and corporations pouring many millions of dollars into efforts to fill short-term home connectivity and device gaps.

While these dollars are almost all aimed at connecting K-12 students to their schools, many policymakers and funders are now taking notice of others who lack the online tools to cope with pandemic isolation and losses -- such as laid-off workers who can’t look for jobs or apply for unemployment compensation, and seniors unable to get regular medical care without internet connections and devices for telehealth services.

Digital inclusion training and support activities are much more difficult when face-to-face classroom facilities are closed or severely limited by social distancing requirements. In Chapter 4 we discuss ways that digital inclusion programs are adapting.

But at the same time, the new environment created by COVID-19 has significantly improved the opportunities for local digital inclusion programs, including those just starting up, to compete for funding and expand potential partnerships—at least temporarily.

Will this improved support environment last beyond the current pandemic emergency? No one can say. What we can predict is that programs will position themselves best for the long run by:

- responding to the crisis in their communities aggressively and effectively,

- engaging and building relationships with newly concerned community and business leaders, and

- leading by example in the areas of best practices, transparency and accountability.

There are two specific strategic approaches by which community digital inclusion programs can significantly improve their chances to gain the outside support they need, both for the immediate pandemic crisis and for the long haul. Those approaches, discussed at greater length in the next two sections are:

- Strategic alliances with business and community institutions and local governments that a) stand to gain directly from the success of digital inclusion work and b) have the ability to fund that work directly and/or to influence the funding decisions of others.

- A systematic, aggressive data strategy for your program to persuasively demonstrate its value...to the people you serve, to the advancement of better-recognized community priorities and to the specific interests of strategic allies suggested in the previous bullet point.

Strategic Alliances

1) Community partners

In thinking through the strategic questions outlined in Chapter 3, it’s important for a start-up program to consider how it can build collaboration with like-minded organizations and leaders into its own leadership structure—whether that means a new organization’s board of directors, a program advisory committee or the partners engaged in a project. There are several good reasons to pay attention to this question. Inviting other organizations to assume some ownership of your program means you can get the benefits of their experience, reputations and social networks; it signals to others in the community, including funders, that you’re operating in a cooperative and transparent manner; and it helps create opportunities for substantive program collaboration.

Even where a new program is being launched within an existing institution that already has a well-established leadership structure—like a public library system—it’s a good idea to ask other organizations to engage with the effort in some way. Partners may bring you new marketing insights and users, help recruit volunteers or provide complementary services to your participants that you can’t. For example, most public library systems aren’t in a position to help their digital literacy trainees acquire refurbished computers or sign up for a discount internet provider, but community partners often can.

Partnership and collaboration with other organizations that care about digital inclusion should be in the DNA of community programs.

PRACTITIONER ADVICE COLUMN

Geoff Millener, The Enterprise Center, Chattanooga, Tenn.: “Our first piece of advice on tackling digital inclusion? It’s to do something.

Chattanooga—a mid-size city in the heart of the South—is Gig City. We’re not Silicon Valley, our metro isn’t in the millions, but our infrastructure is as advanced as anywhere in the world.69 Thanks to EPB, our electric power board and municipal ISP, 10gb/s fiber connections are now available anywhere there is electricity.70

Gig City is so much more than a brand, however. It’s about what that connectivity means, and can mean, for our residents. We know that people have been left out, and will continue to be left out, unless we do something about it—particularly when you consider the breadth of the digital divide between residents with no connection to those moving at gigabit speeds.

There’s no reason to reinvent the wheel (at least not right away), and Chattanooga didn’t—community leaders looked at organizations doing great work across the globe and landed on Boston’s Tech Goes Home71 as a great fit for our community and a practical, replicable way to get started.72

It was an ideal place to begin for a host of reasons, but most importantly was how it explicitly involved other partners in digital inclusion work—more than 80 nonprofits, schools, libraries, churches and neighborhood groups have hosted classes. We knew that digital equity couldn’t be the work of just one organization; it’s too varied and complex for a single entity to manage, let alone solve. Growing a diverse community of digital equity advocates has been central to our community’s successes.73

That network has not only increased the scale of impact, it’s allowed the work to evolve. Our partners at Signal Centers, Inc.74, for example, originally hosted an early childhood Tech Goes Home course. As that relationship grew and their experience and expertise brought to light unaddressed areas of inequity, they became the central partner on a new inclusion effort focused on accessibility and disability services.

Grant opportunities have also been central to this evolution, although not for the most obvious reason. While funding can’t be ignored, the opportunities these application cycles provide for convening wide circles of stakeholders around the table—as well as to include digital inclusion strategies in broader equity efforts—have actually been more important. This approach to collaborative ideation, involving practitioners and participants from the start, continues to develop new partnerships and expand the scope of digital equity and inclusion work in Chattanooga (with or without those original sources of funding). Work around early education, for example, evolved exactly this way thanks to an IDEO challenge we did not win.75

We’ve taken that same multi-stakeholder approach to Smart City work, as well. From community design and involvement in Smart City projects76 to deploying relevant infrastructure, like Wi-Fi nodes77, in ways that can support research or data goals and connectivity within disconnected communities simultaneously. You can tackle both at once, and our experience has shown it actually works better when you do.

Finally, a central piece to the Chattanooga story is the involvement of Hamilton County Schools. A vibrant digital equity ecosystem includes informal learning spaces, but it can’t ignore public schools — they provide robust, nearly universal infrastructure to support equity and inclusion efforts within the most disconnected communities. In 2020, through a long partnership with our schools, we were eventually able to launch HCS EdConnect, powered by EPB, and provide 100Mbps symmetrical service as an inseparable part of a 21st century education.Every student in Hamilton County Schools (HCS) on free or reduced lunch is now eligible to receive high-speed internet at home — at no cost to families 78. The service, HCS EdConnect, was launched to offer immediate assistance for students engaged in distance learning due to COVID-19. But HCS EdConnect also offers a long-term solution, with a commitment from partners for at least 10 more years. While the program may appear to have come together quickly, it’s actually the result of years of vision and intentional partnership building. And that is the Chattanooga story.

From connectivity drives at school registration to deploying advanced gigabit education applications79 in public schools, partnerships with public schools are essential. In preparing this next generation for a future we can’t predict, we must ensure we’re actually closing the digital divide—and not just shifting it80. Full participation in everything this 21st century has to offer depends not just on access to the on-ramps, but control over the destination.

PRACTITIONER ADVICE COLUMN

Tom Esselman, CEO, Connecting For Good, Kansas City, MO

Since 2017, CFG has held an annual ‘State of Digital Inclusion’ Breakfast Event open to the community, as an end of year fund and friend raiser. Each year, the breakfast has a theme designed not only to inform the public about the impact of digital inclusion practitioners, but also to reinforce the trends and topics that are garnering more regional and national support. In 2016 the theme was ‘The Giving Tree--Digital Inclusion As An Ecosystem’ (combining the roots of technology access with the branches of life-improving digital education and skills). In 2017 the theme was ‘MoneySmart--Digital Inclusion In the Financial Community’; and in December of 2018, the theme was ‘Workforce Development-- ‘Digital Inclusion and the Pathways to Paychecks’ The 2019 event theme was ‘Building Resilient Communities’, which unknowingly set us up nicely for the wild year of 2020!

In addition to these annual events, CFG every year chooses community partner projects that expand the awareness and impact of digital inclusion, while broadening our base of community support. Two examples include ‘Cameras For Good’, where we coordinated the selection of a video security company to help high crime neighborhood associations install video cameras in partnership with the prosecutors office and police department; and hosting the annual VITA (Volunteer Income Tax Assistance) program, with financial support from the United Way.

2) Strategic allies and investors

There’s another kind of relationship that could be just as important to your program’s sustainability: Corporations and institutions stand to gain directly from the success of your work (whether they know it or not) and have the resources to make significant investments in that work or to help open doors for those investments from others.

Three industries that meet this criteria are banks, healthcare systems and government, especially social service departments. Are there similar possibilities with other business or public service sectors? Undoubtedly, there are.

The point here is that community digital inclusion programs are, simply by the nature of the work, solving problems and creating value for some industries.

Your program would be wise to put some serious effort into:

- Getting the attention of for-profit and nonprofit entities that would benefit from your digital inclusion work;

- Helping them understand how they gain from your success and

- Making the case for them to invest in your greater success for their own benefit.

Banks

Digital inclusion can empower previously unconnected bank customers to start using online banking tools. This enables their banks to keep them as customers, even while consolidating branches in ways that might make it harder to “bank in the branch.” And a bank’s investment in community digital training or network access may now count (dependent upon the regulatory authority) as a “qualifying activity” for Community Reinvestment Act credit81, which every U.S. bank needs to pass its federal regulatory reviews. Fuller explanations of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and why digital inclusion activities should be a high priority for financial institutions can be found on NDIA’s website.82. Digital inclusion programs are starting to get the attention of some major banks as well as regulators. For the most part, this is still due to the focus of the digital inclusion programs overlapping with priorities of financial institutions, particularly workforce development and education.

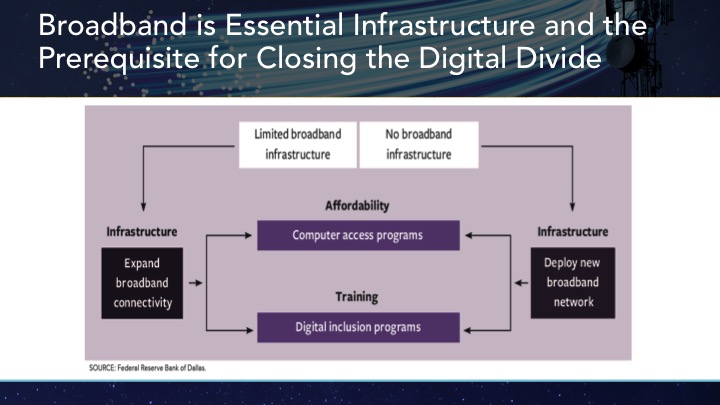

Early advocates of this new resource for digital inclusion efforts include the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, which released Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations in 2016. In it, they asserted, “The CRA provides a significant opportunity to help close the digital divide across communities while simultaneously benefiting financial institutions and improving economic stability.”83 In addition, Fig. 2 provides their visual representation of the “three legs of the stool” of broadband adoption.

Fig. 2. Broadband adoption diagram from: Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations.

Healthcare systems

Digital inclusion can empower thousands of previously unconnected patients in a typical metro area or rural region to research their health-related questions and start using the online patient health record and healthcare management tools offered by most hospitals. Hospital systems have invested many millions of dollars in these tools, and they want their patients to use them—including the low-income patients who are most likely to need training, cheap computers and/or home internet to make that possible84. Healthcare providers are currently working with local digital inclusion programs on digital inclusion collaborations.

In addition, the COVID crisis forced hospital systems as well as community-based health providers—urban as well as rural—to massively shift routine patient services to internet video settings, and it now appears that shift to telehealth will be long-term.

So healthcare providers are increasingly natural allies and partners for community digital inclusion efforts that can “connect the unconnected” among their patients. Healthcare systems can be influential allies for community digital inclusion programs in the quest for funding from third parties, such as foundations. For example:

City of Richmond’s Digital Health Training

The City of Richmond, Calif., partnered with Learner Web, a nationally recognized provider of digital literacy curriculum, to offer a 10-hour web-based bilingual training program that trains learners how to access health information that promote a healthy lifestyle85. A thorough evaluation of the training’s effectiveness is also available free of charge.

Healthcare systems can be influential allies for community digital inclusion programs in the quest for funding from third parties, such as foundations.

Community Tech Network received a grant from Metta Fund, a private health foundation dedicated to San Francisco’s aging population and those furthest from access and opportunity. The grant provides digital literacy and tablets to older adults in San Francisco through a new program called Sunset Tech Connect.86

The Ashbury Senior Computer Community Center partnered with researchers at MetroHealth, the safety-net hospital system in Cleveland, on a pilot MyChart87 patient-portal training program for low-income patients in two clinics, funded by a grant from the Mount Sinai Health Care Foundation. Results were presented at a Gerontological Society of America conference in 2018.

Government, especially social service departments

Local and state government agencies that provide safety net services for lower income residents, disabled residents, senior citizens, unemployed and jobseeking workers, etc. have a lot to gain from helping their unconnected clients to gain internet access and skills. Almost all these agencies have migrated their client services to Web platforms to some extent, and some -- especially state unemployment compensation systems -- now make offline application and mandatory reporting very difficult.

Workforce service agencies need all their clients to have online access for basic job search and application purposes, even when looking for employment where digital skills aren’t actual job requirements. SNAP, Medicaid and family income support programs save money and staff time when clients use their online tools to establish eligibility, apply and “recertify” rather than showing up in agency waiting rooms. Outreach, service scheduling and social support for senior citizen programs and other community-based services is much easier when online tools are available to clients.

All this was all true before social distancing and quarantine shut agencies’ doors and forced clients, especially the most vulnerable, to stay in their homes. Now the pandemic has made internet tools vital for continued delivery of the most basic safety net services.

Community digital inclusion programs that enable residents who use these services to secure affordable connections and devices, and learn to use them, can reasonably look to the agencies involved for partnership and support.

In 2019 Cuyahoga County, OH contracted with Connected Insights, a local nonprofit research organization, to carry out a study of the potential return the county might realize from investing in digital inclusion programs for residents, including family services clients (SNAP, TANF, Medicaid), participants in county-supported senior programs, and other constituents. The completed analysis89 led the County Council to fund a new position to develop digital inclusion collaborations. Subsequently the County has agreed to allow a community wireless broadband provider to install an antenna on the roof of a tall County-owned building, worked with a nonprofit refurbisher to provide computers and hotspots to workforce clients, and played a major role in a digital equity coalition formed in response to the COVID connectivity crisis.

Systematic, Aggressive Data Strategy

Collecting your data and keeping your data so you can tell your story might be the most valuable, least expensive and yet most neglected aspect of starting and managing a new digital inclusion program. Your future ability to plan, manage, fundraise for and report on your program will depend heavily on the quality of the information you’re collecting now.

Whether it’s for reporting to your own board or sponsor, writing a grant proposal, reporting to a funder, telling your story to the media or convincing a strategic ally that you’re worth investing in, you will need to document the people you serve, the value you deliver to them and the impact you have on their lives. You will only be able to document those things if you ask, measure and keep good track of them now, while they're happening.

Program data: Here’s a short list of participant and program data that a digital literacy training program should have in its records.

Participants:

- Contact information

- Relevant demographics

- Home computer and internet status

- How they heard about you

- Why they came—participants’ own goals

- Any specific information needed for partners (for example: participant’s source of health care, food stamp or Medicaid enrollment, school enrollment)

Program: Skills assessment (before training)

- Classes taken

- Skills assessment (after training)

- Help getting a computer?

- Help getting an internet connection?

Your program needs a system to capture this information consistently, accurately and digitally, from Day One. That doesn’t mean you need to have expensive software; information captured on a spreadsheet is fine and can always be moved to a more sophisticated system later. It does mean taking the time to ask participants to share information about themselves and explain why you’re asking for it. It does mean building consistent skills assessments into your training process and recording the results. And it means making sure the information always gets entered in your system while it’s fresh.

Impact data: Once participants have finished your program, you’ll want to know what value the program had for them. Much of that value is going to develop over time. You need a way to ask...not just immediately, but six months, a year or two years down the line.

Some NDIA affiliates accomplish this by means of telephone surveys. If your program serves a lot of people, this might require extra staff cost. If your student base is very big, it might involve some professional help to create a random sample to call. But if you can credibly document a significant impact on the economic, educational, health, civic or social lives of the people who've passed through your program, you’ll find it’s well worth the effort and expense!

In 2012, the Connect Your Community project team designed and led the Adoption Persistence Survey, a large-scale survey of 10,400 program participants nationally that produced one of the largest and most comprehensive datasets representing program participants from a national broadband inclusion program available at the time.88 The survey sample was randomly selected from the programs’ 33,000 trainees and balanced to proportionately represent each of the project’s seven lead partner agencies. A collection of 2,267 completed phone surveys provided insight into program satisfaction, demographic representation, areas of computer use and the impact of the introduction of this new technology on their lives.

This first-ever phone survey designed to measure the longitudinal impact of a digital inclusion training program illustrated the long-term impact of a high-touch community-based training program by measuring previously unconnected participants use of and engagement in online activities of broadband adopters five to six years after completing 30+ hours of basic computer training, obtaining a computer and home internet connection.

PRACTITIONER ADVICE COLUMN

From Dan Noyes, Tech Goes Home

I remember early on in the development of Tech Goes Home someone asking, “What’s your impact?” I recited outputs like the number of graduates and how many new computer we distributed and how many people we got connected. The person paused, and then asked again, “Yeah, but what’s your impact?”

Data work is time intensive, difficult and often nebulous. However, it is incredibly important not only in being able to better tell our story to partners and funders but also in ensuring we are meeting the goals of the organization.

To get at impact, you need to paint a picture (a mother helping her child learn, an unemployed man finding a job, a grandmother video chatting with her grandchildren for the first time) and then use data to support the narrative. The story you tell must have both heartstrings AND data.

Our data collection efforts include an intake survey that captures demographic information and access to technology and relevant skills. A post-course survey informs us what participants learned and explores new levels of engagement. And lastly we do our best to reach all adult participants one year after course completion to discover longer-term impacts of TGH. This is all done via the Internet, text and phone call.

Because of all this, I know that 80% of our families report TGH School was their first time participating in an activity at their child’s school, 35% of TGH Community participants enter the program unemployed and 45% of adult participants’ primary language is not English. All this confirms we are serving the right people and helps paint the clear picture of our participants.

Further, 98% of TGH graduates report that they learned skills during their TGH course that can help improve their lives and 85% of participants without home internet plan to get or got home internet due to TGH. This shows we are meeting our program goals.

Lastly, 93% of students use their TGH device multiple times a week for learning activities, and 84% of adult graduates have used the skills they learned in the program for job-searching and/or at their current job. This tells us we are having an impact on the education and work lives of those we serve.

Each of these pieces of data, along with many more, helps provide evidence about the extent to which TGH accomplishes its goals of improving people’s lives.

“The question digital inclusion practitioners must remember to ask themselves is not always how many computers they have distributed to low-income individuals, families and households or how many digital literacy classes they have held to teach the basics; but has the economic needle really been moved to empower the many still locked into enclaves of impoverishment?” Lazone Grays, Jr., IBSA (Topeka, Kan.)

References

- 68]

- Bill Callahan, Tianca Crocker and Angela Siefer, The Digital Inclusion Coalition Guidebook (Columbus, OH: NDIA, 2017), https://www.coalitions.digitalinclusion.org/

(Back to text)

- 69]

- Dave Flessner, “Gig City milestone: EPB tops 100,000 fiber optic customers,” Times Free Press, October 18, 2018,

https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2018/oct/18/gig-city-milestoneepb-tops-100000-fiber-optic/481343/

(Back to text)

- 70]

- “EPB Fiber Optics Announces Internet Speed Increase,” EPB Optics, updated February 1, 2019, https://epb.com/about-epb/news/articles/epb-fiber-optics-announces-internet-speed-increase

(Back to text)

- 71]

- Tech Goes Home, accessed February 22, 2019, https://www.techgoeshome.org/

(Back to text)

- 72]

- Tech Goes Home Chattanooga, accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.techgoeshomecha.org/

(Back to text)

- 73]

- Rosana Hughes, “Digital education program celebrates 3,000 graduates,” Times Free Press, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2018/jun/18/digital-educatiprogram-celebrates-3000-gradua/473280/

(Back to text)

- 74]

- Signal Centers, accessed March 2, 2019, https://www.signalcenters.org/

(Back to text)

- 75]

- Allison Shirk Collins, “Tennessee, Chattanooga working to narrow the digital divide among early childhood educators,” Times Free Press, February 3, 2019, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/business/aroundregion/story/2019/feb/03/narrowing-digital-divide-among-early-educator/487749/

(Back to text)

- 76]

- Dave Flessner, “Chattanooga collaborative among Top 50 smart city projects,” Times Free Press, January 25, 2019, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/business/aroundregion/story/2019/jan/25/chattanooga-collaborative-among-top-50-smart-city-projects/487420/

(Back to text)

- 77]

- N“I Fell In Love With Chattanooga,” Smart Cities Connect, updated March 2018, https://smartcitiesconnect.org/i-fell-in-love-with-chattanooga/

(Back to text)

- 78]

- “EPB starts signing up students, families for discounted Internet service,” Times Free Press, August 10, 2015, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/business/aroundregion/story/2015/aug/10/epb-starts-signing-students-families-discounted-internet-service/319127/

(Back to text)

- 79]

- The 4K Microscope, accessed March 1, 2019, https://www.4kmicroscope.org/

(Back to text)

- 80]

- Allison Shirk Collins, “Tech at Work: Most elementary age children will eventually work in jobs that don't exist today,” Times Free Press, January 1, 2019, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/edge/story/2019/jan/01/2019-trend-1-tech-work/485558/

(Back to text)

- 81]

- “Community Reinvestment Act (CRA),” Board Of Governors Of The Federal Reserve System, updated December 7, 2018, https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/cra_about.htm

(Back to text)

- 82]

- Bill Callahan, “NDIA to OCC: Let banks seek CRA credit for digital inclusion support,” NDIA (blog), November 25, 2018, https://www.digitalinclusion.org/blog/2018/11/25/ndia-to-occ-let-banks-seek-cra-credit-for-digital-inclusion-support/

(Back to text)

- 83]

- Jordana Barton, Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations (Dallas, TX: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2016), https://www.dallasfed.org/cd/pubs/digitaldivide.aspx

(Back to text)

- 84]

- See Adam Perzynski and Kristen Berg, “Digital Divide Hinders Health-Promoting Technologies,” Public Health Post, April 30, 2018, https://www.publichealthpost.org/research/digital-divide-hinders-health-promoting-technologies/

(Back to text)

- 85]

- “Digital tools for healthier lives,” Digital Health Literacy Project, accessed February 17, 2019, https://www.digitalhealthliteracy.org/

(Back to text)

- 86]

- Jessica Looney, “CTN receives METTA Fund grant to bridge the digital divide for SF seniors,” Community Tech Network (blog), January 4, 2019, https://www.communitytechnetwork.org/blog/ctn-receives-metta-fund-grant-to-bridge-the-digital-divide-

for-sf-seniors/

(Back to text)

- 87]

- K. Berg et al, "Strategies for addressing digital literacy and internet access as social determinants of health," Innovation in Aging, November, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy023.2526

(Back to text)

- 88]

- Samantha Schartman-Cycyk and Valdis Krebs, Adoption Persistence: A Longitudinal Study of the Digital Inclusion Impact of the Connect Your Community Project, (Cleveland, OH: Ashbury Senior Computer Community Center, 2017), http://www.asc3.org/uploads/2/4/9/8/24980903/adoption_persistence_study.pdf

(Back to text)

- 89]

- Samantha Schartman-Cycyk et al, Connecting Cuyahoga: Investment in Digital Inclusion Brings Big Returns for Residents and Administration, Connected Insights, June 4, 2019, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59d3bca38dd041c401d9ed80/t/5d5c448f6fede80001a75334/1566328034944/Connecting+Cuyahoga_2019.pdf

(Back to text)