Chapter 3: Getting started: Three important questions

Question 1. Why do you want to start a digital inclusion program?

A) Who are you? What’s your role in your community, and why is digital inclusion important to you? You might be:

- A librarian who sees crowds of people who need to use public computers.

- A teacher whose students can’t get online assignments done.

- A nonprofit housing manager whose tenants need help to get online.

- A workforce program manager whose clients need digital skills for job placement.

- A family services, senior services or healthcare provider whose clients need computer literacy and access to learn about and access services for which they are eligible.

- A business manager who sees a need for more digitally literate employees or job applicants.

- A local technology advocate looking to enable more citizens to engage with a “smart community” vision.

- A public official or civic policy leader concerned that community members are being digitally left out.

- A neighborhood activist or planner in a neighborhood where many residents are unconnected.

- Or just an independent, concerned individual who wants to help neighbors become more digitally connected.

Whoever you are, it’s important to be aware of the legitimacy and perspective you get from that role, of others in the community who could add their own legitimacy and perspectives as partners and of how your interest and program idea will be received by others based on who “owns” it.

B) What's the digital exclusion issue you want to address in your community? Do you want to focus on a particular population (such as seniors or community members with disabilities) or a particular outcome (such as improving job prospects or accessing health care resources)?

C) Can you describe the impact you would like your program to have? Can you be specific?

The National Digital Equity Center’s Maine Digital Inclusion Initiative5 aims “to provide digital literacy instruction to over 10,000 adult learners each year for the next three years throughout Maine… Digital Literacy assessment and skills training… will increase employability of program participants, improve their job-seeking skills and create a more highly skilled, job-ready workforce across Maine. The program will also help seniors “age in place” by offering classes and workshops on how to use technology tools that will help them remain in their homes, as they grow older.”

Tech Goes Home Chattanooga6 “will continue offering its core programs—focused on early childhood education and the families of young children; on school-age children (K-12) and their families; and on adult residents and workforce needs—providing an estimated 1,030 individuals with 15 hours of age-appropriate digital literacy training, the opportunity to purchase a new device for only $50 and access to low-cost home internet. Tech Goes Home will also scale programmatic offerings developed in FY2019, to including an expanded Early Childhood program, re-focused on supporting families as well as providing professional support for early childhood providers; programming specifically focused on accessibility, creating digital scaffolding alongside the work of disability service organizations; additional Small Business programs serving a diverse community of entrepreneurs; and an expanded Office Ready program, designed to help under- and unemployed residents develop the necessary skills for success in the 21st-century office.”

Question 2. Can you document your community’s need for a digital inclusion program?

Personal experiences and digital exclusion stories are often enough to get an initiative moving. But to target your efforts, clarify goals, build support and develop a strategy, you’ll want to have solid supporting data. Luckily, good local data about household technology access and needs is getting easier to find. Here are some places to start:

- FCC Form 477 Census tract and block data7 (See Appendix 1.)

- U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS) Data8 (See Appendix 2.)

- Any local survey data you can find Library computer-use statistics

- And talk to:

- Workforce program staff

- Housing providers

- County social service staff

Digital inclusion program planners in some communities have carried out their own survey research with local residents, three of which are the City of Austin, City of Seattle and the City of Fayetteville.

Austin Digital Assessment Project9 [Austin, Texas]

In the heart of Texas, the City of Austin partnered with the University of Texas’ to administer a citywide assessment of local households’ access and use of information and communication technologies in 2014. The self-administered mail and online survey was delivered in English and Spanish to 15,000 randomly selected households, including a 20 percent oversampling of low-income households to ensure adequate representation from economically disadvantaged groups. Survey results were statistically adjusted to be generalizable to the Austin population. Findings affirmed residents possessed higher-than-national-average technology adoption. Despite these findings, significant gaps in use and access were reported for the estimated 50,000 digitally divided households. The results were reported by geographic area, race and ethnicity, among a number of metrics. The assessment report was released concurrently with the city’s Digital Inclusion Strategic Plan, providing data and strategy guidance for community stakeholders engaged in digital inclusion programming. Sample topical areas include places of access, reasons for non-adoption, online activities and information sources.

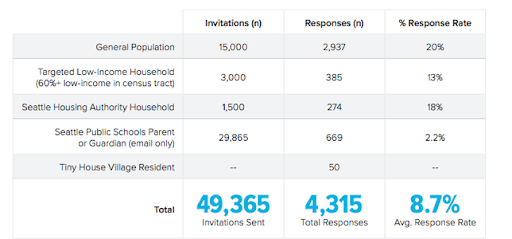

Technology Access and Adoption Study10 [Seattle, Washington]

The City of Seattle announced results from its fifth citywide digital inclusion survey in early 2019. The survey design was co-created through a series of discussions with community leaders and representatives of the city’s technology advisory board. Using a combination of random and non-random sampling techniques (Fig. 1), nearly 20,000 residents were solicited to complete the bilingual Spanish and English survey either on paper or online, with the option to contact support services by phone for assistance in completing the survey. Results from the study showed a significant five-year increase in internet access among residents from 85 to 95 percent and an average monthly household internet cost of $150. Emphasized in the 20-page survey report were key barriers to access and adoption, such as unaffordability and frustration with the quality of internet access. The city’s council president noted that “it is vital for us to conduct a digital equity study every few years to truly understand the pulse of the city’s digital access.” Sample topical areas include online use and skills, tech support, privacy and security concerns, civic engagement, training needs and barriers to adoption.

Fig. 1. Methodology and sampling graphic from: 2018 Technology Access and Adoption Study.

Digital Use and Access Survey11 [Fayetteville, Arkansas]

The City of Fayetteville partnered with a group of engaged citizens and local leaders representing education and the private sector to distribute its inaugural 2019 survey of citywide digital equity. The survey, which is currently being deployed at the time of this guide’s printing, will be delivered in English and Spanish to a random sample of households for completion online or via paper formatting. Any interested resident can participate in the study by visiting the Speak Up Fayetteville website. City leaders note additional plans to promote survey completion through a combined effort of media engagement, public events and distribution via the public library system. The concise 23-question survey assesses home internet access, digital-device ownership, digital skills and technology interests. Results from the study will reportedly be used to inform the city’s development of a digital-equity strategy to drive the development of digital inclusion programming to address documented needs.

Question 3. What’s the organizational setting for the program you hope to start?

The basics of digital inclusion are similar in all settings. Important aspects of your digital inclusion initiative—including decision-making, resources, program objectives, training priorities, desired outcomes, metrics and constituent relationships—will vary depending on your sponsoring organization, operating style and goals.

So...which of these settings are you planning for?

A) Digital inclusion programming inside a community institution or established organization

- Library Housing authority

- Social service agency

- Community organization

- School

- Some other institution or organization

Digital inclusion programming in support of another program agenda

- Workforce training

- Adult literacy

- Health services

- Financial literacy

- Public childhood education

- Some other kind of existing program

C) A stand-alone community digital inclusion program

If the answer is “standalone community digital inclusion program,” then who’s the “owner”? Is there a sponsoring organization in place, or do you plan to create one?

This is vitally important if you plan to raise and spend money to support the program. It’s less vital but still important if you’re thinking about an all-volunteer, no-major-expenses operation.

Even if you don't need significant funding, you probably still need an organizational structure to:

- Get and keep your partners and volunteers engaged;

- Protect yourself and others from personal liability;

- Attract in-kind donations of equipment and supplies;

- Attract monetary donations and

- Create the kind of community presence and support you want.

If you want your donors to be able to deduct their donations, then you require a nonprofit corporation with a functioning board of directors and an IRS-confirmed charitable tax status such as 501(c)(3), with the ability to comply with government reporting requirements, accounting standards, employment laws, etc.

You can learn more about setting up a nonprofit organization at: National Council of Nonprofits12 and Nolo's guides to starting a nonprofit13, including a state-by-state guide.

For a new digital inclusion program, the process of designing, organizing, incorporating and (if necessary) raising money for a standalone sponsoring organization will take a lot of effort and time before you’re in a position to start your work.

It’s often simpler to begin as a project of an existing institution or program with the possibility of spinning off an independent program if that makes sense at a later time.

The right path for your initiative will depend not just on its goals but on the particular opportunities and obstacles you find in your community—especially the people you may want or need to work with and the resources you find available. Make the effort to meet those people and explore those resources.

Taking the time to answer these basic questions—to your own satisfaction and the satisfaction of prospective allies and partners—will put you in a much stronger position to plan an appropriate, effective digital inclusion strategy for your community.

References

- 5]

- “Maine Digital Inclusion Initiative,” National Digital Equity Center, accessed March 5, 2019, http://digitalequitycenter.org/our-strategies/ (Back to text)

- 6]

- Tech Goes Home Chattanooga, accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.techgoeshomecha.org/

(Back to text)

- 7]

- “Fixed Broadband Deployment Data from FCC Form 477,” Federal Communications Commission updated December 12, 2018, https://www.fcc.gov/general/broadband-deployment-data-fcc-form-477

(Back to text)

- 8]

- Note: ACS Table B28002 provides data on households with cable, DSL or fiber broadband accounts—i.e., conventional “wireline” connections—vs. households for whom mobile devices are the sole home internet service. This distinction is important because mobile subscriptions are far more likely to have strict data usage limits and the devices they connect, especially smartphones, also have serious limitations in important use categories like education.

(Back to text)

- 9]

- Sharon Strover, Joe Straubhaar, Karen Gustafson, Wenhong Chen, Alexis Schrubbe and Paul Popiel, Digital Inclusion in Austin, (Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, Technology and Information Policy Institute, 2015), http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Telecommunications/Digital_Inclusion_in_Austin_April_2_2015.pdf

(Back to text)

- 10]

- Seattle Information Technology Department, 2018 Technology Access and Adoption Study, (Seattle: City of Seattle, 2018), http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/Tech/City%20of%20Seattle%20IT%20Technical%20Report%20v17b.pdf

(Back to text)

- 11]

- “Digital Inclusion Plan,” Speak Up Fayetteville, City of Fayetteville, Ark., accessed Feb. 12, 2019, https://speakup.fayetteville-ar.gov/digital-inclusion-plan

(Back to text)

- 12]

- How to Start a Nonprofit,” National Council of Nonprofits, accessed February 15, 2019, https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools-resources/how-start-nonprofit

(Back to text)

- 13]

- “Nonprofits.” NOLO, accessed February 23, 2019, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/nonprofits

(Back to text)