Chapter 5: Affordable internet access

True digital inclusion requires “affordable, robust broadband internet service” without having to leave home. Users should have access to sufficient bandwidth to manage the full range of normal online applications and tasks, including K-12 and post-secondary schoolwork, job search, health record access, online banking and commerce, social media and reasonable access to entertainment sources, at home. This means the ability to use the internet via desktop or laptop, not just a smartphone, and to do so without oppressive data caps. Households should be able to maintain this quality of broadband access at a cost they can manage without undue financial hardship.

These modest standards are very difficult to meet with commercial ISP service. In most U.S. communities where broadband is readily available, a basic home internet account (cable or DSL) costs between $55 and $85 a month.29 This is clearly beyond the financial reach of many lower-income households. According to the U.S. Census American Community Survey, only 51% of U.S. households with incomes below $20,000 had home broadband subscriptions (including mobile data plans) in 2017, compared to more than 90% of those with incomes above $75,000.30

Helping community members to get internet access at a cost they can afford is probably the most challenging digital inclusion goal a community can undertake. Local digital inclusion programs have responded to this challenge in dozens of ways, any of which may provide a useful example for your efforts. Generally they fall into the following broad categories:

- Helping eligible community members to find and sign up for discount Internet programs, where that’s possible;

- Providing free public access computers and Wi-Fi access inside public facilities; and

- “Community networking,” including

- Free Wi-Fi access in public spaces

- On-commercial, free or affordable networks serving specific groups of community members, like tenants in a particular public housing estate

- Large-scale public network initiatives that create new broadband options for entire communities.

- Encourage resident services representatives at housing authorities to talk to their residents about discount internet offers during community events or when new residents move into their housing units.

- Attend parent/teacher events at schools as a method of reinforcing written materials sent home with students.

- Speak directly with community members who use public computers in spaces such as the public library or community centers.

- An adequate internet connection from a provider whose terms of service permit you to share it;

- An off-the-shelf Wi-Fi router/access point mounted somewhere that’s fairly accessible (i.e., without major obstructions) to the prospective users;

- A place to plug the router in; and

- A plan for managing the equipment and users’ access to it (e.g., creating and sharing a password.)

- You need a source of internet service whose terms of service do not forbid you to share access with users outside the premises to which the account is registered. Most ISPs’ terms of service do include that prohibition. If the Wi-Fi is meant to be available beyond your yard, parking lot or front sidewalk, you could have a contractual problem with your ISP.

- You need a place to mount your access point(s) that’s within the antenna’s effective range of the intended users (no more than 400-500 feet, usually less); with as little foliage or other obstacles, especially metal, in the path from antenna to users; and able to be connected to your internet and to a power source. If you can cover the area you want to “light up” by putting a router/access point inside a window overlooking the area, you may be home free. (Glass doesn't impede Wi-Fi.) Otherwise you'll have to think about more complicated solutions like exterior antennas, mesh networking and power-over-ethernet. These aren't necessarily expensive, but they add some set-up complexity and network management issues. This is where you or someone in your group may need to learn some new skills.

- If you build it, they’ll probably come—maybe lots of them. Consumers have gotten used to checking for Wi-Fi availability to avoid cell phone data charges. Heavy use by people you don’t know may be exactly what you want, but it means that your public Wi-Fi must be managed. Someone needs to check it regularly to make sure it’s operational, that its capacity is reasonably consistent with its user load and that the use is generally within appropriate guidelines. There are tools available for this purpose.

- 29]

- Bill Callahan and Angela Siefer, Tier Flattening: AT&T and Verizon Home Customers Pay a High Price for Slow Internet (Columbus, OH: NDIA, 2018), https://www.digitalinclusion.org/blog/2018/07/31/tier-flattening/

(Back to text) - 30]

- “Table B28004,” 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, updated November 28, 2018, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2017/5-year.html

(Back to text) - 31]

- Bill Callahan, Angela Siefer, Alisa Valentin, Daiquiri Ryan and Benjamin Austin, The Discount Internet Guidebook (Columbus, OH: NDIA, 2018), https://www.discounts.digitalinclusion.org/

(Back to text) - 32]

- Public Libraries in the United States: Fiscal Year 2015 (Washington, DC: Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2018), https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/publications/documents/plsfy2015.pdf

(Back to text) - 33]

- “Managing Public Computers,” WebJunction, updated August 2, 2018, https://www.webjunction.org/explore-topics/public-computers.html.

(Back to text) - 34]

- Community Technology Network, “Computer Lab Installation Checklist” http://nonprofithousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/Toolkits/Broadband/CTN_CompLabInstallChecklist.pdf

(Back to text) - 35]

- “How to Build a Computer Lab,” wikiHow, accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.wikihow.com/Build-a-Computer-Lab

(Back to text) - 36]

- Preston Rhea, “How to Create a Public Computer Center,” Open Technology Institute (blog), New America, June 7, 2011, https://www.newamerica.org/oti/blog/how-to-create-a-public-computer-center/

(Back to text) - 37]

- Elliot Harmon and Sarah Washburn, “Public Computing Resource Center,” TechSoup, updated April 12, 2012, https://www.techsoup.org/support/articles-and-how-tos/public-computing-resource-center

(Back to text) - 38]

- “Library Privacy Guidelines for Public Access Computers and Networks,” American Library Association, updated June 24, 2016, http://www.ala.org/advocacy/privacy/guidelines/public-access-computer

(Back to text) - 39]

- “Public WiFi.” Office of the Chief Technology Office, Washington, D.C., accessed February 17, 2019, https://dc.gov/service/public-wifi

(Back to text) - 40]

- “How Wicked Free Wi-Fi Works,” City of Boston, accessed February 16, 2019, https://www.boston.gov/departments/innovation-and-technology/wicked-free-wi-fi

(Back to text) - 41]

- “San Francisco WiFi,” City and County of San Francisco, accessed February 18, 2019, https://sfgov.org/sfc/sanfranciscowifi

(Back to text) - 42]

- ConnectHome, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, accessed March 4, 2019, https://connecthome.hud.gov/

(Back to text) - 43]

- “Playbook 6: Connectivity Strategies,” ConnectHome, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, accessed March 4, 2019, https://connecthome.hud.gov/playbook/three-legged-stool/connectivity-strategies/

(Back to text) - 44]

- “dcConnectHome, Connect.DC-Digital Inclusion Initiative, accessed March 5, 2019, https://connect.dc.gov/dcconnecthome

(Back to text) - 45]

- “Mesh Network Playbook,” Fresno Housing Authority, accessed March 4, 2019, https://sites.google.com/view/fresnohousingmeshnetwork/home

(Back to text) - 46]

- Bridging the Digital Divide, (Cleveland, OH: Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority, n.d.), accessed March 5, 2019, http://www.cmha.net/enewsletters/stakeholder/ConnectHomeBrochure.pdf

(Back to text) - 47]

- DigitalC, accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.digitalc.org/

(Back to text) - 48]

- “Connect the Unconnected Program,” DigitalC, accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.digitalc.org/connect-the-unconnected-program

(Back to text) - 49]

- Community Networks (Blog), Institute for Local Self-Reliance, accessed February 1, 2019, https://muninetworks.org/

(Back to text) - 50]

- Next Century Cities, accessed February 3, 2019, https://nextcenturycities.org/

(Back to text) - 51]

- See Community Network’s article about NetBridge’s 2015 launch at https://muninetworks.org/content/epb-and-chattanooga-will-lower-price-internet-low-income-students

(Back to text) - 52]

- Representatives of Greenlight and the Wilson Housing Authority discussed this initiative in depth in a 2017 Community Networks podcast, https://muninetworks.org/content/wilson-greenlight-public-housing-authority-solve-access-gap-community-broadband-bits-episode

(Back to text) - 53]

- Free & Low Cost Internet Plans, https://www.digitalinclusion.org/free-low-cost-internet-plans/

(Back to text)

Helping eligible residents sign up for available discount internet services

AT&T, Comcast, Charter Spectrum, Cox, Altice and some smaller internet service providers currently offer home broadband at discounted rates for certain low-income customers. Eligible groups of consumers vary among the providers, and the offers are, of course, limited to the respective providers’ wireline service areas.

Details of these and other discount internet programs can be found in NDIA's Free & Low Cost Internet Plans page.53

Where discounts exist, community digital inclusion programs have found that sign-up assistance can be an effective tool to help some low-income consumers get affordable home connections.

From NDIA’s Discount Internet Guidebook31:

There are various methods that organizations use to get community members to sign up for discount internet offers. Many of the tactics work in tandem with each other and are not as effective in a siloed method. For example, flyers, leaflets and other signage do not work well alone. They are simply a gateway to getting the word out about the discount internet offers or they reinforce verbal conversations.

It is very important to meet community members who are in need of these services in trusted spaces. Some examples include:

Interpersonal communication is very important at these events. Community members must trust the messenger in order to have a meaningful conversation about low-cost internet offers. Many practitioners stated that simply having a representative from the ISP at community events is not a strong method for acquiring participants in discount-internet offers programs. The discount internet offers are designed to help a specific population and require one-on-one consultation.

Providing free internet access sites inside community facilities

In most communities the library is the first place community members turn when they need a public-access internet computer—and for good reason. U.S. libraries maintain hundreds of thousands of public workstations that provide their patrons with hundreds of millions of user sessions annually. For instance, in FY 2015, public libraries reported 294,319 public-access Internet computers and 300.65 million user sessions.32 They also typically offer fast, free Wi-Fi access inside their buildings and often make laptops or tablets available to patrons so they can take advantage of it.

There is an extensive literature of operational and policy guidance for library public-access facilities. A good place to start exploring is WebJunction.33

Local organizations and institutions other than libraries sometimes decide to create free computer and internet access inside their facilities. These include low-income housing providers, community social service and recreation centers and community-based technology programs, among others. In some cases these efforts serve specific groups, such as tenants, program clients or trainees rather than the broad public; in other cases they're intended for the general public but in a particular underserved neighborhood or community. A computer lab created primarily for a training program or for students on a campus might offer “open lab hours” as a public service for the neighbors.

In a COVID-19 era, it will be up to you to responsibly follow social distancing best practices from information gathered from your local government and respected health officials. If you are opening, or re-opening a public Wi-Fi center, make sure that your organization has the capacity for proper PPE, and frequent cleanings. More information can be found in the checklist table in Chapter 4.

If your digital inclusion program is considering setting up a new public access computer lab and you haven’t done it before -- or even if you have -- we recommend starting with the Community Technology Network’s “Computer Lab Installation Checklist”.34

Two other good but quite different introductions to setting up a computer lab are wikiHow’s “How to Build a Computer Lab: 15 Steps (with Pictures)”35, and “How to Create a Public Computer Center” from New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute.36

Other resources offering more tips and tricks:

Free Wi-Fi access in public spaces

Community members who have personal internet devices, but not internet access at home, can benefit significantly from free Wi-Fi service in public places like parks, civic and commercial areas, public buildings like recreation centers, community college campuses, transit stations and stops, and so on.

Free public Wi-Fi enables people with mobile internet devices—including the many low-income people who have smartphones but very limited data—to use internet sites, services and apps without regard to data charges. Free public Wi-Fi also expands access for people who have laptops or tablets but no home internet access (including many low-income students in schools with one-to-one device programs).

Created by public institutions

While not a substitute for affordable home broadband, reliable free Wi-Fi in public spaces can be a valuable interim digital inclusion tool for local governments and other institutions that control those spaces and can include public access points in their overall technology plans and budgets. Of course that tool is more effective if “connected public spaces” are widely distributed, especially in communities where they’re most needed, and are made convenient and safe for users.

Many city governments have installed public Wi-Fi in public service areas such as city hall and recreation centers. Some have been more aggressive.

Examples - Public access Wi-Fi provided by local governments

Washington, DC’s municipal government has deployed more than 600 Wi-Fi hotspots for public use throughout the city, including exterior hotspots in many locations including city parks. There’s a map on the DC.gov website as well as free smartphone apps to help community members and visitors find a hotspot.39

The City of Boston’s “Wicked Free Wi-Fi” includes 299 public access points at locations throughout the city.40

San Francisco provides public Wi-Fi in 32 “parks, plazas and open spaces.”41

Institutions with campuses like community colleges, which often have exterior Wi-Fi service for their students and employees, can create a valuable access opportunity for other community members, either by extending the range of their networks to public “edge” areas or by welcoming the public for on-campus use.

Cleveland’s Cuyahoga Community College offers both on-campus and extended “guest” access for the public on its Metro Campus, located in the neighborhood with the greatest concentration of public housing in the city.

Public libraries, whose Wi-Fi is designed for public use inside their buildings, often find that they’ve inadvertently created exterior hotspots as well, with users on their steps or in their parking lots after hours. This creates a dilemma for many library leaders: Safety and security (Do we want people gathering around the library when we’re not here to supervise?) vs. need and public service (People without home internet access, especially students, need to do online tasks at times when we're not open, and it’s appropriate and easy for the library to make that possible.) Some have decided to make the best of an opportunity.

“We know our Wi-Fi in the parking lot is an access point after we close for people who do not have internet access at home. We also have a charging station outside.”

Debbie Saunders, Executive Director, Bossard Memorial Library, Gallipolis, OH

If you’re investigating digital inclusion strategies on behalf of a local government, a library system or another public institution, it’s worth taking a hard look at your opportunities to create free public Wi-Fi opportunities using the spaces and network resources at your disposal.

Other digital inclusion advocates—community leaders and ordinary citizens—shouldn't hesitate to ask the leaders of your community’s public institutions to look for those opportunities. After all, you’re the public.

Created by nonprofit organizations and individuals

Control of public spaces and existing networking capacity mean that municipalities and other public institutions are often the natural candidates to deploy and support public hotspots, but they are certainly not the only ones doing so. Community-based organizations, business associations and even individuals have taken the lead to create public Wi-Fi opportunities in many communities.

As many small-business owners can attest, offering free Wi-Fi to everyone in a small area is pretty straightforward. You just need:

There are costs and work involved, but nothing that the average consumer technology user can’t handle.

Transferring that simple process to a public hotspot is harder than it looks.

Small-scale non-commercial, free or affordable networks

In the absence of other truly affordable home internet options, digital inclusion initiatives have long included the creation of non-commercial networks to provide home broadband access for apartment complexes, small neighborhoods and the like. While most of these small community networks are based at least partly on Wi-Fi, there are are recent examples that use LTE cellular systems as well as varieties of DSL.

Public housing authorities provide free home Internet access for their residents through local networks in a number of communities—either supporting initiatives by nonprofit partners, or building and maintaining networks themselves. This trend has been encouraged since 2014 by the Department of Housing and Urban Development's “Connect Home” initiative42, whose “Connect Home Playbook”43 characterizes the approach as: “Free wireless internet reaches every unit (like a dorm or hotel).”

Examples - Small-scale non-commercial, free or affordable networks

The Connect Home Playbook points to a project of Washington, DC’s dcConnectHome initiative44 in which the DC government and the DC Housing Authority wirelessly linked over 1,700 residents to free internet service through DC-Net, the municipal broadband network.

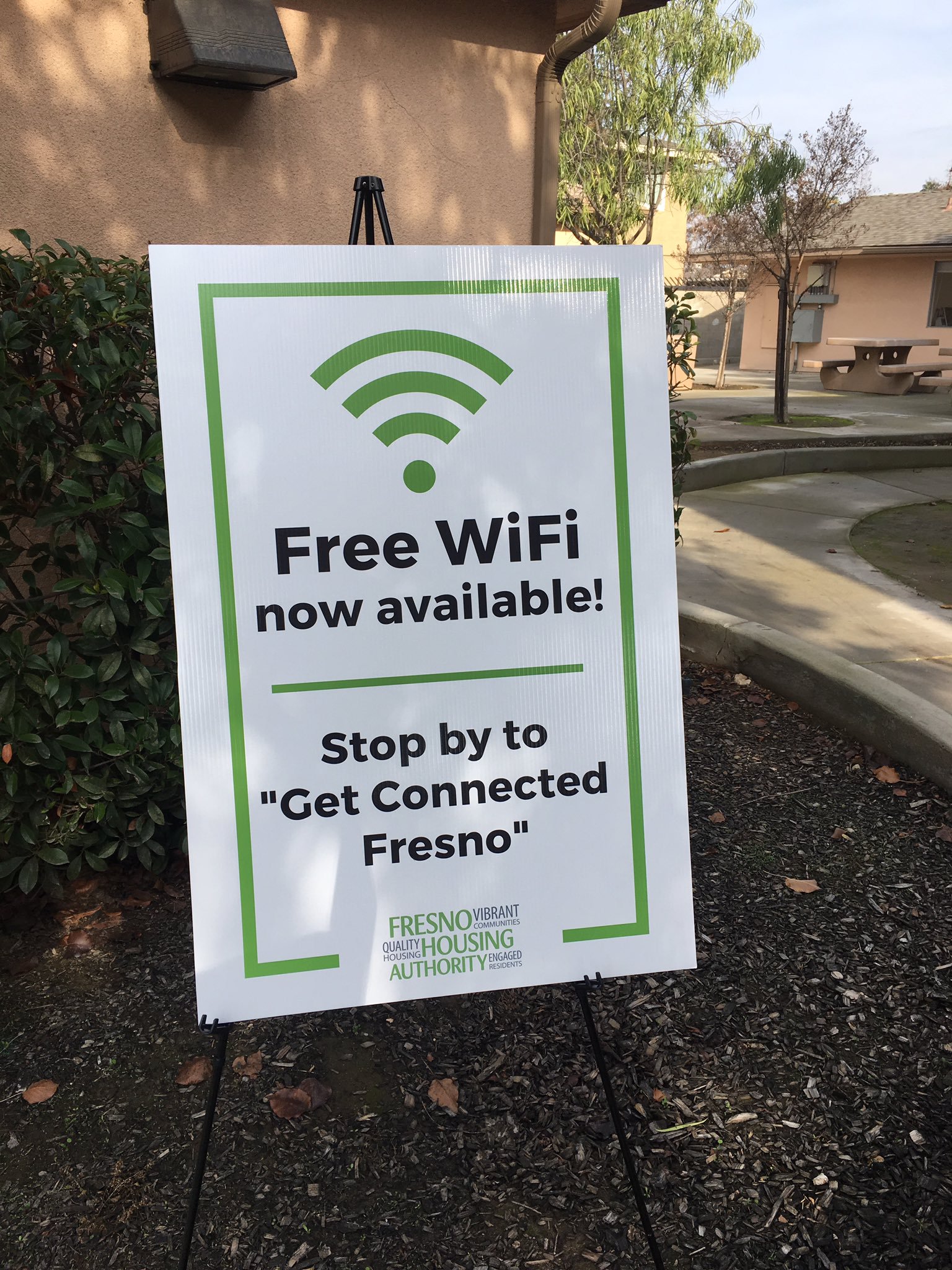

The Fresno (CA) Housing Authority is deploying a mesh Wi-Fi network as part of its “GetConnected Fresno” initiative. The network currently provides free internet service for 554 housing units in 64 buildings at six FHA properties. Its internet connection comes from Central Valley Independent Network, a local independent fiber ISP. Fresno Housing Authority recently published a “Mesh Network Playbook” which shares its networking model in detail.45

The San Antonio Housing Authority (SAHA) has deployed free Wi-Fi hotspots in 197 units in three apartment buildings, as well as fifty community rooms, and plans to provide similar connections for more than six hundred additional units in 2019. 2,800 SAHA tenants will have Wi-Fi in their units by the end of 2019. More about SAHA's effort, including its "Smarti" solar-powered Wi-Fi prototype, can be found in Appendix 4.

Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority46 (CMHA), as part of its “Cleveland Connects” initiative, partners with nonprofit DigitalC47 to bring free or affordable broadband to 460 residents in three CMHA apartment buildings. The partners use a roof-to-roof millimeter-wave wireless network to connect each building to an independent fiber ISP at gigabit speeds, then share that connection with residents in their units, using either Wi-Fi or enhanced DSL technology over the buildings’ internal copper phone lines.48

Large-scale public broadband network initiatives

The U.S. has recently seen an nationwide explosion of new, local public or nonprofit internet service providers. These come in a variety of sizes and technologies, but the most common is a public enterprise—often a municipal utility or rural cooperative—serving a small city or rural area with very fast internet service delivered through an optical fiber network. These local public broadband services aren't necessarily affordable and don't automatically promote digital inclusion for low-income community members. But some are finding ways to do exactly that.

A comprehensive overview and up-to-date coverage of the national community broadband movement is provided by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance at its “Community Networks” website.49

Another valuable resource is Next Century Cities. They represent and support hundreds of cities across the country that are building or operating community-owned broadband, developing policies to govern private 5G deployments and pursuing next-generation broadband for their communities in other ways.50

Both Community Networks and Next Century Cities help highlight community-owned networks that adopt digital inclusion as a goal, using their locally controlled systems to create new, affordable high-speed internet options for low-income community residents. Two of the best-known municipal fiber networks, in Chattanooga, Tenn., and Wilson, N.C., offer models for other communities interested in this approach.

The cheapest regular residential service offered by Chattanooga’s EPB municipal fiber utility costs $58 a month for a 300 Mbps connection. That’s a very good deal but not affordable for many lower-income Chattanooga households. State law severely restricts the ability of EPB and other city utilities in Tennessee to offer lower-cost services to low-income customers. But in line with its priority of using its network to support education, Chattanooga has created a special option for families of about 20,000 students in the Hamilton County schools who are enrolled in the free- or reduced-price lunch program: “NetBridge,” which delivers EPB’s lowest-speed fiber connection for a much more affordable $27 a month.51

The City of Wilson’s “Greenlight Community Broadband” fiber network has a standard internet-only option of 50 Mbps for $40 a month. Through a partnership with the Wilson Housing Authority, that service is offered to tenants in Housing Authority units for just $10 a month.52